Art Keeps the Native American Culture Alive

Utah artist Al Groves launches a new art collective as he works to keep indigenous traditions alive.

In the center of Al Groves’s home, he works on his beadwork. His children pass by frequently asking questions, which allows Al to alternate between being a parent and practicing his artistic connection to his culture. While he tends to his children, he also tends to his art. It’s no coincidence that his work station is easily accessible to his family — it helps his children learn and live their culture as urban Native Americans.

Al and his wife, Amanda, are raising their four children in Springville, Utah. Living in a small town without the concentrated influence of the Native community can make it difficult to pass on important traditions, which is one of the reasons why Al regularly invites his children to learn about their culture. (Read: "Get to Know Utah's Tribes")

Most recently, Al has expanded his aims with the launch of Turtle Island Art Collective, a digital marketplace to showcase the work of Native artists. I’m here to photograph and interview Al because as a Navajo photographer who grew up in the Salt Lake City area, I want to learn about how he was able to integrate his heritage and his art.

"While he tends to his children, he also tends to his art. It’s no coincidence that his work station is easily accessible to his family — it helps his children learn and live their culture as urban Native Americans."

Al Groves works on his beadwork at home as his children look on.

Al Groves’s beautiful, intricate Ute artwork is receiving attention due to his practice of porcupine quillwork, which some consider to be a dying art.

Groves uses porcupine quills to create woven embellishments.

Al’s father worked in education for the Northern Ute Tribe, but the Groves family didn’t live on the reservation. His parents taught him the importance of education and pride in his Native American heritage. He went on to attend Brigham Young University.

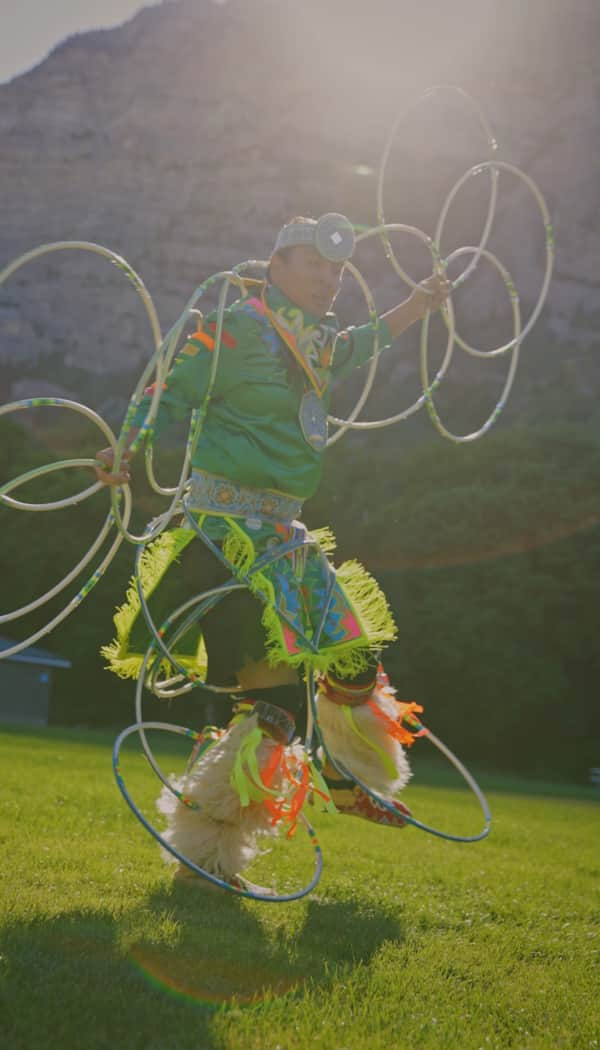

Along the way, he attended Native American pow wow gatherings, but never participated or competed in dancing. After the birth of his first child, he began reconnecting to his culture out of a strong feeling of responsibility. Now he draws upon the medium of art to teach basic Native principles and philosophy to his family and others.

Al is of two different Native American tribes: Northern Ute and Hopi. His beautiful, intricate artwork is receiving attention due to his practice of Native American porcupine quillwork, which some consider to be a dying art. This practice is similar to Native beadwork, but uses porcupine quills to create woven embellishments.

“Al Groves is a unique artist because he reaches to both his Hopi and Ute tribes for inspiration for his work,” says Dustin Jansen, director of the Utah Division of Indian Affairs. “Whatever medium Al chooses, you will recognize geometry and symbolism from the Southwest, and designs from the northern plains and Rocky Mountain regions. Al has put in the work to become accomplished in both beading and quill work. His work is appreciated and purchased by Native and non-Native people throughout the United States and Canada.”

Al prioritizes education at home and at work, as a health teacher and basketball coach at Mountain View High in Orem, Utah. His family regularly volunteers to present school assemblies around the state about Native American history, much-needed voices in a place that doesn’t teach students the complete story of its indigenous peoples.

Al believes that education and perspective are catalysts to true growth and understanding. In a world full of distractions and social problems, simply sharing Native American truths can be enlightening.

Groves didn’t live on the reservation growing up, but his parents taught him the importance of education and pride in his Native American heritage.

Photo: Samuel Jake

"In a world full of distractions and social problems, simply sharing Native American truths can be enlightening."

"There are so many ways to ‘be Native.’ Some people come from more of a traditional background and others are given more of an urban experience. All are an important part in this modern story of the Indigenous. All stories will be needed to succeed in passing this culture on to future generations."

– Al Groves

Groves named the Turtle Island Art Collective for the term that First Nations people call North America, based on a creation myth. Utah is home to eight federally recognized Native tribes, among the 562 tribal nations across the country. Al describes the collective as a digital marketplace showcasing Native artists, while it also serves as a resource to help others appreciate — and invest in — indigenous culture.

The collective currently spotlights the work of eight Native American contributors, but Al plans to add more artists from different backgrounds so that Native artists will receive profits from selling their artwork. “One thing that would be awesome is that we can create a digital marketplace where the artists are selling things directly,” he said.

As an urban Native myself, I found that my path is very similar to that of Al Groves. As a young Navajo kid, I didn’t learn dancing, drumming or beading, and as I’ve matured I have felt a void in my life. At times, I’ve felt like I’m not Native enough.

Hearing Al Groves’ story gave me hope about reconnecting with my culture. “It doesn’t matter when I start as long as I begin the journey,” is a quote I appreciate from Al’s Instagram posts. I love how that thought made me feel.

“There are so many ways to ‘be Native,’” Groves says. “Some people come from more of a traditional background and others are given more of an urban experience. All are an important part in this modern story of the Indigenous. All stories will be needed to succeed in passing this culture on to future generations.”

As I spoke with Al in his home, I realized that passing on the culture begins and ends with desire. The culture is what builds relationships in the community and makes them stronger. Al expressed his gratitude to those who taught him, and says he would not be where he is today without their generosity. Native American culture suggests that the bonds between people are connected by the respect and practice of the arts. (Read: "The Navajo Basketmakers")

This is a responsibility we have to each other as Native Americans, while the same could be expressed about any indigenous culture. Al Groves is a strong leader in the Native community. As I continue to learn the ways of my ancestors, I desire to have my culture be as centrally rooted in my life as it is for Al.

Groves launched the Turtle Island Art Collective digital marketplace to showcase the work of Native artists.

Photo: Samuel Jake